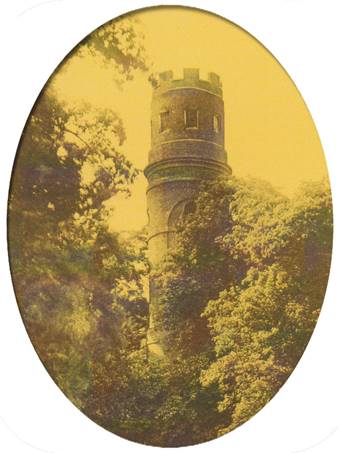

Strattons Tower - The Cromwell Connection

Stratton’s Tower appears to have been built in 1789, for John Stratton, Esq., of “Gays” (now known as “The Gage”), Little Berkhamsted, but the materials from which it was built – the bricks, the stonework, and at least some of the timbers – were salvaged from a very large and very much older building, known as “The Brewhouse,” but known also, from 1622 to 1703, as the “Mansion House for the Manor”. It was rated in the Michaelmas 1662 Hearth Tax Return at 16 Hearths (rooms large enough to justify a fireplace), twice the size of the next largest dwelling in the village.

It is almost certain that at least some of these materials were as much as 250 years old when the Tower was built, making them approaching 500 years old at the present time.

The bricks

The bricks can clearly be seen to be the product of cottage industry. They are of varying sizes and hand-made: many can be seen to have been fired when the material was too wet, at least one bears the imprint of small fingers, probably a child and another, the imprint of the claws of a small animal, possibly a pet cat or kitten.

(c.1534-1540)

There is a Great Pit, largely hidden in a wooded area, just about 250 yards from the site of the demolished house, and this pit was quite probably the source of the material for the bricks and is probably the “Sandpit Close (2 acres)” included in the 1703 Private Act of Parliament for the sale of the Brewhouse.

There is a slideshow of the great pit here (opens in a new tab)

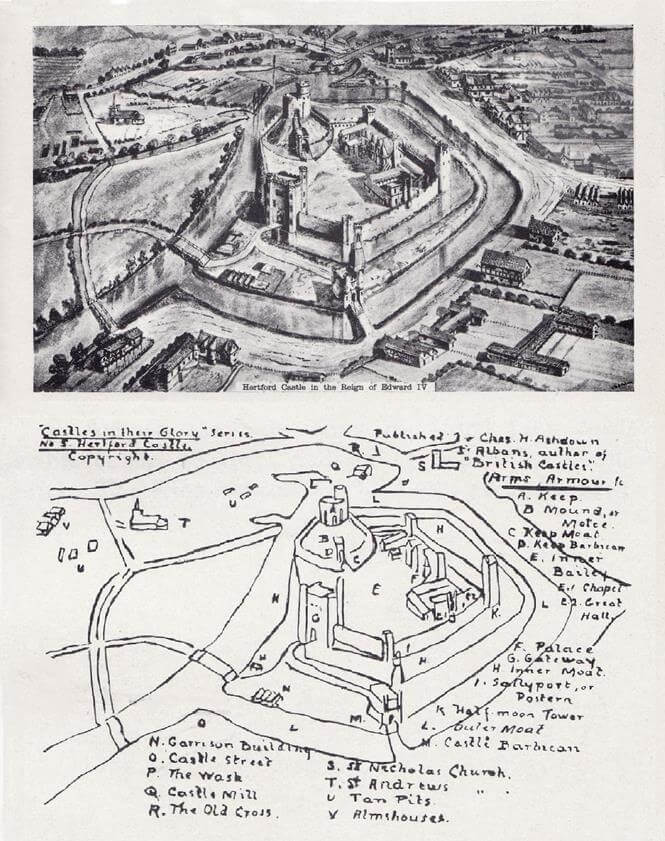

Hertford Castle

No direct documentary evidence appears yet to have been discovered as to for whom or why the house was built but the circumstances suggest that it could have been intended for Thomas Cromwell and/or his nephew, Richard Williams, who, in 1534, were appointed joint Constables of nearby Hertford Castle, to serve as a base, separate from the Castle, but close to it, just four miles away.

After his succession to the throne in 1509, Henry VIII spent considerable sums turning Hertford Castle into a civilian palace, including building the gatehouse, the only part which still stands, other than parts of the Curtain Walls and the original Mound.

He was a constant visitor to the Castle: he was there on 10th November 1522 and he commissioned a survey of the condition of the building, which showed that a thorough repair was necessary, after the completion of which, in November 1524, the Queen, Katherine of Aragon, held Court there, with the King present.

The only part which still stands – now Hertford Town Council Offices

The King’s next visit was in June 1528, and in 1530 he spent Sunday 4th September and the following three days there.

The King finally parted from Queen Katherine on 14 July 1531, and late in 1533 her daughter, the Princess Mary, spent a short stay at the Castle, before joining her half-sister, the Princess Elizabeth, at Hatfield House, in December. The Princess Elizabeth, the daughter of Anne Boleyn, was scarcely three months old when she was sent to Hatfield, following an Order in Council dated 2 December 1535.

The two Princesses both became Sovereign of England, Princess Mary becoming Queen Mary I (1553-1558) and her half sister the Princess Elizabeth succeeding her, becoming Queen Elizabeth I (1558-1603).

Thomas Cromwell

Thomas Cromwell could be described as King Henry VIII’s “fixer” and, in 1534, when he was at the height of his influence, he was appointed Constable of Hertford Castle – jointly with his nephew, Richard Williams, the son of his elder sister, Katherine, who had married Morgan Williams, a Welsh lawyer.

Richard later took the surname Cromwell, and his great-grandson was Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector of England (including Wales), Scotland and Ireland (whose name would otherwise have been Oliver Williams).

Constable of Hertford Castle was then an important role, Hertford Castle being the place where the two Princesses, Mary and Elizabeth, were often kept.

Princess Mary must have been moved back from Hatfield later, as she wrote a letter to the King on 2 October 1536 and various other documents have survived which indicate that the two Princesses, Mary and Elizabeth, were in residence at the Castle during the period from July 1537 to December 1540 (until after Cromwell’s attainder and death, on 28 July 1540.)

By 22 December 1539, the Princess had removed to Enfield and Cromwell brought the Duke there to be introduced to her; however, with the downfall of Cromwell the following June, the marriage plans came to an end.

(Main Source: The Chronicles of Hertford Castle by Herbert C. Andrews, MA, FSA - 1947)

During this period, Cromwell’s appointments in the local area had been as follows:

1534 - 27 February: Appointed Joint Constable of Hertford Castle and Hertingfordbury, as well as Keeper of the Park at Hertingfordbury.

1535 - 14 May: Appointed Bailiff of Enfield, Middlesex.

1535 - 16 May: Appointed Steward and Bailiff of the Manors of Edmonton and Sayesbury, Middlesex.

Then, in 1538, he was granted the Advowson of the Church in Little Berkhamsted (in effect, the right to appoint the local village priest) but he held that right for only two years, until he was deprived of all of his rights and properties shortly before his decapitation on 28 July 1540.

“in 1538 the site and possessions of the Priory, (of Lewes) including the Advowson of Little Berkhamstead, were granted to Thomas Crowell but reverted to the Crown on Cromwell’s attainder.”

(Source: Notes on the History of Little Berkhamstead Church – Collected by C.E. Johnston. 1908, page 9.)

Before Cromwell’s appointment as Constable of Hertford Castle, Lord Mountjoy had been Lord of the Manor of Little Berkhamstead but he died in 1535, and Bedwell and Little Berkhamstead passed to his daughter Gertrude, wife of Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter and Second Earl of Devon, who was first cousin of Henry VIII.

The Marquis was executed for high treason in 1539 and his widow attained and her lands forfeited but she was pardoned in 1540. She lived until 1557 but Bedwell and Little Berkhamstead were never restored to her and remained in the possession of the Crown until December 7, 1539, when Henry VIII granted for life to Anthony Denny, chief gentleman of his Privy Chamber, the stewardship of the manors of Bedwell and Berkhamstead and the custody of the mansion of Bedwell and of Bedwell Park.

Henry VIII died on 28 January 1547 and Sir Anthony Denny was one of the King’s executors and also one of the guardians of Edward VI, and was therefore in an excellent position to secure grants of lands for himself and on June 28, 1547, the Crown granted to Sir Anthony Denny and his heirs for ever "in full absolute and entire completion and execution of our dear father’s mind and intention" the manors of Bedwell and Berkhamstead.

Sir Anthony died on September 1, 1549, but the two manors remained in the Denny family until 1600, when his grandson, Edward, sold the manor of Little Berkhamstead, to Humfrey Weld, Esq., Alderman of London, who was knighted in 1603 and was Lord Mayor of London 1608-9.

His summer residence was Arnold’s, in Southgate, Middlesex, and in 1641, his grandson, also Humfrey, purchased the Lulworth estate in Dorset, where the family still live.

(Source: Notes on the History of Little Berkhamstead Church – Collected by C.E. Johnston. 1908, page 9.)

There had been one historic precedent, some three centuries earlier:

Before Cromwell’s appointment as Constable of Hertford Castle, Lord Mountjoy had been Lord of the Manor of Little Berkhamstead but he died in 1535, and Bedwell and Little Berkhamstead passed to his daughter Gertrude, wife of Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter and Second Earl of Devon, who was first cousin of Henry VIII.

Sir John Weld

After Thomas Cromwell’s similar, but more terrible “sudden fall from grace” in 1540, there appears to have been no one single individual or family in the area, of sufficient wealth or influence, to occupy the “great house”, presumably because the person who had commissioned the building was no longer willing or able to occupy it and such records as have been discovered show it changing ownership quite frequently.

“This house is first mentioned in 1597 when ‘John Langdale, yeoman, enfeoffed (1) to Thomas Steward of London, Pewterer, The Brewhouse and 2 acres at Little Berkhamsted, on the occasion of his marriage to Elizabeth, daughter of John Langdale.’ Langdale appears in a Manor Court Roll of 1554, but the house was probably much older.”

(Source: Gerald Millington LITTLE BERKHAMSTED (A History of a Hertford Village), Page 16.)

(1) enfeoffed Feoffment or enfeoffment was the deed by which a person was given land in exchange for a pledge of service. This mechanism was later used to avoid restrictions on the passage of title in land by a system in which a landowner would give land to one person for the use of another. The common law of estates in land grew from this concept. (Wikipedia)

As mentioned above, the earliest transaction so far discovered was in 1597, then the ownership changed again, only six years later, in 1603, to Thomas Shadbolt, and yet again ten years later, 1613, to Nicholas Hooker and his son William, and it may have been at least at some time in “multiple occupation”: as when the then Lord of the Manor, Sir John Weld, of Arnold’s Court, Southgate, Middlesex, purchased it in 1622, it was from several owners (Nicholas and William Hooker and others).

However, as the name Langdale appears in a Manor Court Roll of 1554, it is not impossible that the Langdale family had owned or occupied the house for many years, although it seems unlikely that a yeoman could afford to own and maintain a house with sixteen hearths.

After Thomas Cromwell’s similar, but more terrible “sudden fall from grace” in 1540, there appears to have been no one single individual or family in the area, of sufficient wealth or influence, to occupy the “great house”, presumably because the person who had commissioned the building was no longer willing or able to use it and it may have been at least at some time in “multiple occupation”: when the then Lord of the Manor, Sir John Weld, of Arnold’s Court, Southgate, Middlesex, purchased it in 1622, it was from several owners (Nicholas and William Hooker and others).

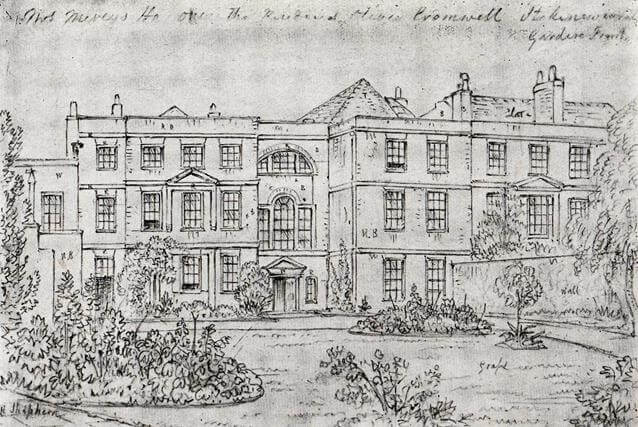

Like most of his predecessors, Sir John had been an absentee Lord of the Manor, his main residence being quite a small house, Arnold’s Court, in Southgate, in the Parish of Edmonton and the County of Middlesex, which had been his father’s “Summer Residence”.

The name Arnold’s or Arnold’s Court later “evolved” into the present Arnos Grove, although that house was built by James Colebrook, a London mercer, who had purchased property in Southgate from 1716 and built the new house between 1719 and 1723, as a larger replacement for Arnold’s Court, a short distance to the east of the earlier house, where he continued to live until the new house was completed, when the old house was demolished.

Sir John had referred, in his Last Will and Testament, to Arnold’s Court as being very small, “my mansion house is very small”, certainly in relation to his father’s grand “Weld House” in London – and he must have had a very similar opinion of the “Old Manor”, in Little Berkhamsted, judging by its present appearance.

Therefore the reason for his purchase of The Brewhouse, was quite probably not only to have made it the Mansion House for the Manor of Berkhamstead Parva, but also to have made it, with its 16 substantial rooms, his main residence, which would have replaced Arnold’s Court in Southgate, had he not died so soon after as February 7 in the following year.

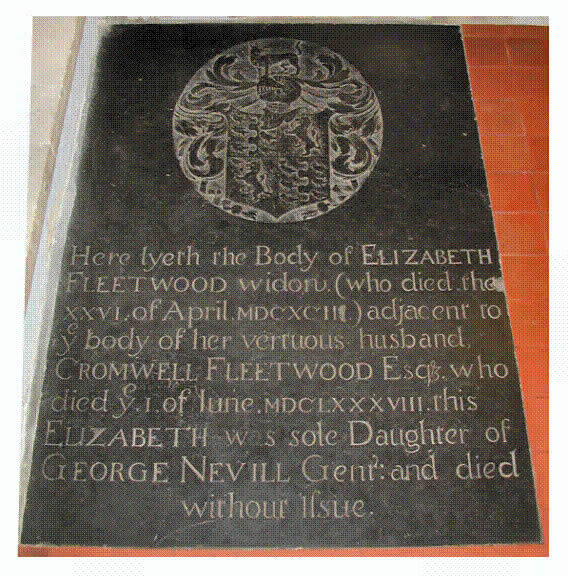

Sir John Weld incorporated the house into the Manor estate, making it the “Mansion House” for the Manor, but it must be nothing more than a coincidence that, in 1679, Elizabeth Nevill, who inherited the Lordship of the Manor from her father and would most likely have lived in the house, married Cromwell Fleetwood, who was the grandson of Oliver Cromwell, the Lord Protector, and therefore a direct descendant of Richard Williams (later Richard Cromwell), who had been appointed joint-Constable of Hertford Castle with Thomas Cromwell in 1534.

Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell’s eldest daughter, Bridget, (Biddy to her father), also the eldest of her siblings to survive into full adulthood, had married Henry Ireton, Cromwell’s premier General, but on 26 November 1651 he died of the plague, in Ireland, after the siege of Limerick, and the summer of the following year, 1652, Bridget, his widow, married General Charles Fleetwood, himself just recently widowed. Fleetwood also succeeded Ireton as Commander-in-chief of the Parliamentarian forces in Ireland and Lord Deputy of Ireland.

Bridget Cromwell (1624-1662)

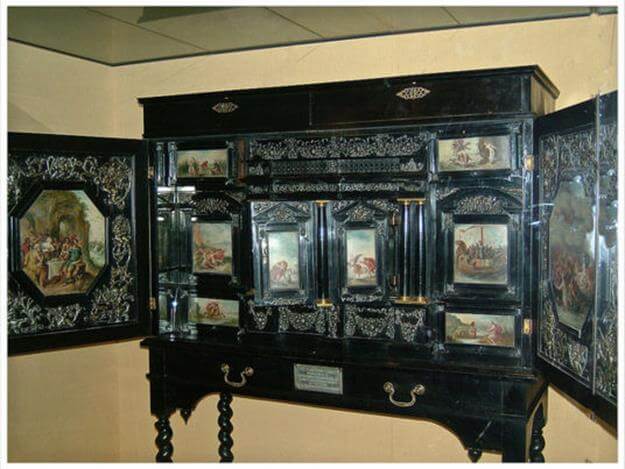

The Fleetwood cabinet

On Bridget’s marriage to Fleetwood, her father, Oliver Cromwell, he gave her, as a wedding present, a rather splendid cabinet, which can still be seen today in the National Museum of Ireland, in Dublin.

(The provenance of the “Fleetwood Cabinet” is included at the end of this Section.)

(Both Generals Ireton and Fleetwood were buried in Bunhill Fields, the Non-conformist Burial Ground in City Road in the City of London, as are, quite coincidentally, several members of the Stratton Family, including John, who gave his name to the Tower in Little Berkhamsted.)

Charles Fleetwood was born in 1618, a younger son of Sir Miles Fleetwood of Aldwincle, on the River Nene in East Northamptonshire, and had been admitted a member of Grays Inn in 1638, as his son, Cromwell Fleetwood, is believed to have done also, after the Restoration.

However, Fleetwood had committed to the Parliamentary cause in 1642, together with other young gentlemen of the Inns of Court, and entered the Earl of Essex’s lifeguard and by 1644 he had risen to the rank of Captain, in command of a regiment in the Earl of Manchester’s army.

General Fleetwood was Member of Parliament for Marlborough and, as well as Lord Deputy of Ireland, he was a Member of Oliver Cromwell’s Commonwealth’s Council of State, Major-General of Cambridgeshire, Essex, Hertfordshire, the Isle of Ely, Norfolk, Oxfordshire and Suffolk.

Fleetwood had been regarded as a likely successor to Oliver Cromwell, and it is said that Cromwell had in fact nominated him as such, but he himself chose to give his support to Oliver’s son, Richard Cromwell, who did succeed his father as Lord Protector of England, Scotland and Ireland, following his father’s death on 3 September 1658 but he was in office only until 25 May 1659, just 264 days.

After the Restoration, Charles and Bridget Fleetwood were allowed to live quietly in London. Fleetwood had been debarred from public office but as he had taken no part in the Regicide (the trial and execution of Charles I) he was otherwise left unmolested, although the body of one of their children, Anne, who had died in infancy and been buried within Westminster Abbey, was one of those exhumed at the Restoration, although her remains were spared the obscene public mutilation visited on the bodies of Oliver Cromwell and his associates, including Ireton.

Not surprisingly, Bridget died young, in June 1662, and she was buried in St Anne’s church, Blackfriars. She was survived by at least seven children; Fleetwood was father of at least three of them and Ireton had been the father of the rest.

Bridget had had four children by her first marriage, to Ireton, all of whom survived into adulthood, and at least three by her second marriage, to Fleetwood, one of whom, the eldest, was Cromwell Fleetwood, the other two being Anne, who had died very young, and Mary, who in 1677 married Nathaniel Carter, a merchant of Great Yarmouth and lived until 1722.

After Bridget’s death, Fleetwood soon married again, to Mary Hartopp, and moved into her house in Stoke Newington, bringing with him seven children, his two children by his first wife, Frances Smith, Smith Fleetwood and Elizabeth Fleetwood, as well as Bridget’s five surviving children.

This house stood on the northern side of Stoke Newington Church Street and was probably built about 1625, around the end of reign of James I and beginning of the reign of Charles I; it was the largest house in the district and the name was changed to “Fleetwood House” following Fleetwood’s marriage to Mary Hartopp in 1664.

Cromwell Fleetwood was born in 1653 and had therefore been just four or five years old when the Lord Protector died and about eleven years old when he moved with his father into Fleetwood House, where he probably continued to live for the next fifteen years.

Cromwell Fleetwood died without issue in 1688, and his widow in 1692, and they are buried together in the Chancel in Little Berkhamsted Church. Their grave is covered by a large stone just inside the Communion rails, on the south side of the Church, with an inscription and the arms of Fleetwood quartering Nevill.

St Andrews Church, Little Berkhamsted

After the death of Cromwell Fleetwood’s widow, the former Elizabeth Nevill, the Manor of Little Berkhamstead was left to George Nevill, eldest son of Mrs. Fleetwood’s cousin and heir-at-law, John Nevill of Ridgewell, Essex, when he should come of age, and, until such time, the revenue, after meeting her debts and legacies, was to go to John Nevill.

The revenue from the Manor, however, eventually proved insufficient to meet the charges upon it and in 1703 the trustees obtained a Private Act of Parliament to enable them to sell a portion of the estate, which included the “Mansion House” for the Manor, which was described in the Act as “very large and a burthen to the estate to keep up”, to meet those charges.

The house passed through several owners during the 18th century until it was acquired by the Stratton family, in about 1787: John Stratton then had it demolished and most of the Tudor hand-made bricks, and some of the stonework and timbers, were re-used in the construction of the Tower.

There is other evidence of Thomas Cromwell’s building impressive manor houses:

Although Thomas Cromwell was arraigned under a bill of attainder and executed for treason and heresy on Tower Hill on 28 July 1540, “as early as December 1540, the king had shown favour to Cromwell’s son Gregory by creating him Baron Cromwell of Oakham and summoning him to Parliament as a peer of the realm. The following February, Henry had granted him some lands in Leicestershire that had been owned by his late father. These centered on Launde Abbey, a lavish manor house that the elder Cromwell had started building on the site of an Augustinian priory. Gregory would live there with his family for the rest of his days...”

(Thomas Cromwell by Tracy Borman, Page 397)

Timeline

| 1599 | Oliver Cromwell born, a direct descendant of Katherine, the elder sister of Thomas Cromwell. |

| (Thomas Cromwell, Chief Minister to King Henry VIII from 1532 to 1540, was beheaded in 1540.) | |

| 1603 | Elizabeth I, last of the Tudors, died – succeeded by James I (VI of Scotland), the first of the Stuart Kings of England, Scotland and Ireland (England then included Wales). |

| 1618 | Charles Fleetwood born, the third son of Sir Miles Fleetwood, a prominent official at the Court of Wards. |

| 1624 | Bridget Cromwell, first daughter of Oliver Cromwell, born. |

| 1625 | James I died, succeeded by his son, Charles I. |

| 1642 | The English Civil War broke out. |

| 1646 | Bridget Cromwell, aged about 22, married General Henry Ireton, Lord Deputy of Ireland. |

| 1648 | Parliament’s New Model Army consolidated its control over England. |

| 1649 | King Charles tried for high treason, convicted, and beheaded (109 years after Thomas Cromwell). |

| 1651 | General Henry Ireton Lord Deputy of Ireland died, in Ireland, of plague. |

| 1652 | General Charles Fleetwood appointed Commander-in-Chief in Ireland. |

| Bridget Cromwell, aged about 28, married General Charles Fleetwood, Commander-in-Chief in Ireland. | |

| On the occasion of her marriage to General Fleetwood, Oliver Cromwell gave his daughter an “ebony cabinet, decorated with paintings by Old Franks and silver repoussée work (ornamented with patterns in relief made by hammering or pressing on the reverse side). | |

| The couple presumably resided, with the Cabinet, at Fleetwood’s Official Residence, Wallingford House, which stood in Whitehall, on the site of the present Admiralty: at the Restoration the house reverted to George Villiers, 2nd Duke of Buckingham. | |

| 1653 | Oliver Cromwell appointed 1st Lord Protector of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland, and Ireland. |

| 1653 | Cromwell Fleetwood, son of Bridget and Charles Fleetwood, born, presumably at Wallingford House. |

| 1662 | Bridget Fleetwood died, aged 38, and either her husband or her son, Cromwell Fleetwood, inherited the Cabinet, which had come to be known as “The Fleetwood Cabinet”. |

| 1664 | Following the death of Bridget Fleetwood, Charles Fleetwood married Mary Hartopp, daughter of Sir John Coke and widow of Sir Edward Hartopp and he then moved, together with the numerous children from their various marriages, including Cromwell Fleetwood, then about eleven year old, and “The Fleetwood Cabinet”, into her house, Hartopp House, in Church Street, Stoke Newington, which then became Fleetwood House. |

| 1679 | Cromwell Fleetwood, then aged 26, married Elizabeth Nevill, who succeeded her father, George Nevill, to the Lordship of the Manor of Little Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, and the Cabinet would have become part of the furniture at the Mansion House (also known as “The Brewhouse”). |

| 1688 | Cromwell Fleetwood died intestate and the Fleetwood Cabinet passed to his widow, Elizabeth. |

| 1692 | Charles Fleetwood died, in October, so it would have been possible for him to have visited his son or even to have attended his burial, in St Andrews Church in Little Berkhamsted. |

| 1692 | Cromwell Fleetwood’s widow, Elizabeth, died and, after about 13 years at the Mansion House, the Cabinet passed to her first cousin, Sarah Burkitt, and through her family, until 1902, when it was inherited by Miss Frances Margaret Andrews of Dublin, who died in 1931. |

| 1931 | A clause in Miss Andrew’s will read: |

| “I bequeath to the Trustees of the National Gallery of Ireland the cabinet known as the ‘Fleetwood Cabinet,’ which was presented by the nation to the daughter of Oliver Cromwell on her marriage to General Fleetwood...” (“Notes and Queries,” 1932.) |

“The Fleetwood Cabinet”, below, is still on public view at the National Gallery of Ireland, in Dublin.

Main Source: The Chronicles of Fleetwood House – by A. J. Shirren (1951)

“Fortuitous Source”: a typing mishap in Google brought up a page of a young woman’s Flickr, with photos of her recent holiday, in Ireland, which included a visit to the National Gallery of Ireland – where the Cabinet is on display – and it is the photo from her Flickr page which is shown above.)

The Provence

from

The Chronicles of Fleetwood House

by A. J. SHIRREN (1951)

(from the foot of Page 175 and continued on Page 176)

Postscript

Just before Christmas last year, 2016, a new, though somewhat tenuous, connection between Thomas Cromwell and Little Berkhamsted was established, when Penny and Tony Tyndale took up residence in the village, as Tony is a direct descendant not of William Tyndale but of William Tyndale’s brother, (coincidentally, as Oliver Cromwell was a direct descendant not of Thomas Cromwell but of Thomas Cromwell’s elder sibling, Katherine.)

It has been said that the rationale for Henry VIII to break the Church in England from the Roman Catholic Church in 1534 was a copy of William Tyndale’s treatise, The Obedience of a Christian Man.

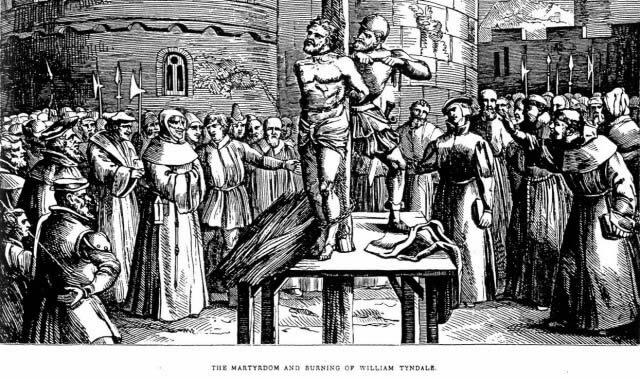

Even so, when Tyndale was in the Low Countries In 1535, he was betrayed and seized in Antwerp, charged with heresy and held in the castle of Vilvoorde (Filford) outside Brussels, for over a year, until In the autumn of 1536, he was condemned to be burned to death, despite Thomas Cromwell’s intercession on his behalf: he “was strangled to death while tied at the stake, and then his dead body was burned”.

(The penalty for heresy was to be burnt at the stake but strangulation was a merciful interpretation of that sentence, since it meant that the victim was not actually burnt alive.)

His dying prayer was that the King of England’s eyes would be opened, which appeared to be answered just two years later when Henry authorised the Great Bible for the Church of England, which was largely Tyndale’s work – with missing sections filled by translations by Miles Coverdale.

The Tyndale Bible, as it came to be known, played a key role in spreading Reformation ideas across the English-speaking world.

(Main Source: Wikipedia)

Thomas Cromwell, a man of confirmed Protestant sympathies, had supported Tyndale and contacted the Vilvoorde prison governor in an endeavour to get him released but although that failed, Thomas Cromwell was successful later in convincing King Henry to approve the distribution of the English Bible, translated by Tyndale and completed by Miles Coverdale.

(Source: Christian History Institute)